Multivitamins come in various forms, from traditional tablets and capsules to gummies and powders, catering to different preferences and dietary restrictions. Their portability makes them an ideal travel companion.

Why are Multivitamins Essential for Travellers?

The stress of travelling can cause discomfort like a stiff neck, sore muscles, back pain, and joint aches, which can be quite tiring. Multivitamins can soothe these symptoms besides providing the essential vitamins and minerals that could be deficient in your diet throughout your journey. Besides this, multivitamins can prove beneficial in several other ways:

•Supporting Natural Wellness: Multivitamins are a blend of vitamins and minerals usually found in our food. They are beneficial for bridging nutritional gaps and naturally improving health. One daily multivitamin during travel can serve as a reliable support system, countering the deficiency of essential nutrients induced by changing diets.

•Alleviating Stress: Changing time zones and long flights can disrupt our sleep patterns and leave us fatigued and stressed. B vitamins, particularly B6, B12, and folic acid, play a substantial role in stimulating the nervous system for combatting stress. Including these nutrients in a multivitamin can help travellers manage fatigue and adjust to new time zones more effectively.

•Supporting Healthy Eating on the Go: Irrespective of whether your travel is business-related or for leisure, the challenge of maintaining a healthy diet on the move is undeniable. Sustaining healthy eating habits is typically easier within familiar routines but not while exploring new environments. Thus, consuming health supplements or multivitamins during travel can play a crucial role in balancing irregular meal patterns. Things to Keep in Mind

Different types of travel may require specific nutritional support. For example, an adventure-packed outdoor expedition might demand higher nutrients to support physical endurance, while a business trip could necessitate optimal cognitive function and stress management. Multivitamins to cater to these varying needs, ensuring travellers get the right nutrients for their journeys. However, travellers must consult a healthcare professional or a registered dietitian before choosing a multivitamin. Healthcare practitioners can help identify specific nutrient deficiencies or health concerns and guide travellers in selecting the appropriate multivitamin.

The author is the CEO, Co-Founder, PositiveGems.

Medically Speaking

Nutritionally Nourishing Traditions: Savouring Classic Delights of Ganesh Chaturthi

One of India’s favorite celebrations, Ganesh Chaturthi, gathers people to celebrate and show their devotion to Lord Ganesha. While the event is known for its delicious sweet and Savory foods, it also presents an opportunity to choose food with awareness. Ganesha has an endless list of his favorite foods. Every year around Ganesh Chaturthi, Hindu households create an incredible spread of dishes for their beloved Lord Vinayak.

•Murmura Jaggery Laddoo is a favorite food of lord Ganesha. This food was so uncontrollable when Kubera invited him for a meal. The lavish meal didn’t satisfy Lord Ganesha, who wanted more to eat. It was said that Lord Shiva proposed offering some puffed rice to him. It was assumed that his appetite was satisfied immediately after that. For this reason, Murmura jaggery laddoo is made and served to Lord Ganesha.

•Ukadichemodak is the healthier form of modak is the ukadichemodak. Rice flour that has been cooked retains more nutrients and has fewer calories. The filling made of coconut and jaggery is an excellent source of fiber and vital mineralsand helps maintain the haemoglobin level.

•Puran Poli made with chana dal, jaggery, and cardamom.Chana dal offers fiber, is a significant source of protein, may lower cholesterol, and includes calcium, zinc, and folate. Sugar, jaggery, and plain flour are sources of carbohydrates.

•Coconut rice has various health advantages and a great flavour. It contains a lot of good fats, especially medium-chain fatty acids, which the body can easily absorb and utilize as fuel.

•Besan Laddoo are made from besan(Chickpea), Sugar , ghee and dryfruits. Besan is rich in complex carbohydrates and has a low glycemic index. Dry fruits are rich in potassium, magnesium, calcium, zinc, phosphorus, and vitamins like vitamins A, D, B6, K1, and E.

•Dry Fruit Ladoo is the either combine crushed or finely chopped nuts with dried fruits and a binder like dates or figs. They give us both vital nutrients and energy.

People with diabetes should be mindful before consuming high-caloric food. Jaggery is healthier than sugar, contains essential minerals like potassium and iron, and has slower digestion, which aids in keeping blood sugar levels checked.

Celebrating tradition and spirituality during Ganesh Chaturthi while eating foods that are good for your health is possible. When prepared carefully, these classic recipes have nutritional benefits and are delicious. We may enjoy the festival delights while feeding our bodies by adopting these time-tested recipes with a contemporary touch.

Dr Anish Desai is MD, Clinical Pharmacologist and Nutraceutical Physician, Founder and CEO, IntelliMed Healthcare

Solutions.

Alzheimer’s disease is a devastating neurodegenerative disorder that affects millions of people worldwide, causing progressive cognitive decline, memory loss, and changes in behaviour and personality. Alzheimer’s disease is a brain ailment that gradually impairs thinking and memory abilities as well as the capacity to do even the most basic tasks. Symptoms of the late-onset variety typically begins to show in the majority of patients in their mid-60s. Rarely, early-onset Alzheimer’s strikes between the ages of 30 and 60.

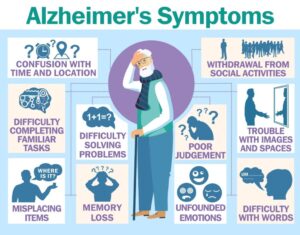

Symptoms:

Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease characterized by memory loss, difficulty in planning, decision-making, and problem-solving, as well as mood swings, depression, anxiety, and increased irritability. It can lead to difficulty in locating objects, misplaced items, and disorientation. Personality changes may include withdrawal from social activities and apathy, affecting hobbies and interests.

Causes and Risk Factors:

While the exact cause of Alzheimer’s disease is not fully understood, several factors have been identified as potential contributors:

Age: Advancing age is the greatest known risk factor. The majority of Alzheimer’s cases occur in individuals aged 65 years and older.

Genetics: Family history can play a role. Certain genes, such as APOE ε4, are associated with a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s.

Brain Changes: Alzheimer’s is characterized by the accumulation of abnormal protein aggregates in the brain, including beta-amyloid plaques and tau tangles.

Cardiovascular Health: Conditions that affect heart health, like high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol, may increase the risk of Alzheimer’s.

Lifestyle Factors: Lack of physical activity, poor diet, smoking, and limited cognitive stimulation are also considered potential risk factors.

Treatment:

While there is currently no known cure for Alzheimer’s, research suggests that there arecertain steps individuals can take to delay its early onset and promote brain health. By adopting a healthy lifestyle and making certain choices, you can potentially reduce your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Stay Mentally Active: Engaging in mentally stimulating activities can help keep your brain active and sharp. Activities like reading, puzzles, crossword puzzles, chess, and learning new skills or languages can challenge your cognitive abilities and promote brain health. Staying mentally active throughout your life may help reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s.

Stay Physically Active: Regular physical activity has numerous benefits for brain health. Exercise improves blood flow to the brain, reduces inflammation, and supports the growth of new brain cells. Aim for at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity exercise per week. Activities like walking, swimming, and dancing can be enjoyable ways to stay physically active.

Eat a Brain-Healthy Diet: A well-balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats can support brain health. Omega-3 fatty acids found in fish, such as salmon and walnuts, have been associated with lower Alzheimer’s risk. Antioxidant-rich foods like berries, leafy greens, and nuts can also protect brain cells from damage.

Manage Stress: Chronic stress can contribute to cognitive decline and increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Practicing stress-reduction techniques like meditation, deep breathing exercises, yoga, or mindfulness can help lower stress levels and support overall brain health.

Get Quality Sleep: A good night’s sleep is essential for cognitive function and memory consolidation. Aim for 7-9 hours of quality sleep per night. Establish a regular sleep schedule, create a relaxing bedtime routine, and make your sleeping environment comfortable and conducive to rest.

Stay Socially Engaged: Maintaining social connections and engaging in meaningful relationships can help keep your brain active. Social interactions stimulate cognitive function and may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s. Join clubs, volunteer, or spend time with friends and family to stay socially engaged.

Manage Chronic Conditions: Certain chronic health conditions, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and obesity, have been linked to an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Managing these conditions through a healthy lifestyle, medication, and regular check-ups can help reduce your risk.

Stay Mentally Emotionally: Mental and emotional well-being play a crucial role in brain health. Practices like mindfulness, meditation, and relaxation techniques can help reduce anxiety and depression, which can contribute to cognitive decline.

Challenge Your Brain: Engage in activities that challenge your brain regularly. Try new hobbies, take up a musical instrument, or learn a new language. The more you challenge your mind, the more you can potentially delay cognitive decline.

Seek Professional Advice: If you have concerns about your cognitive health or a family history of Alzheimer’s disease, consider seeking guidance from a healthcare professional. Early detection and intervention can make a significant difference in managing the disease’s progression.

In conclusion, delaying the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease involves adopting a brain-healthy lifestyle. By staying mentally and physically active, eating a nutritious diet, managing stress, and maintaining social connections, you can potentially reduce your risk and promote long-term brain health. Remember that these steps can be beneficial not only for your brain but for your overall well-being as well.

The author is the Director & Head of Department-Neurology Sanar International Hospitals.

Meniere’s Disease was first described by Prosper Meniere in 1800s. It is characterized by episodes of giddiness, tinnitus and hearing loss or fullness in the ears. It may be preceded by an aura of twinkling in front of eyes, heaviness in head etc. Each episode typically lasts for few minutes to hours. The symptoms are likely to be worse as the episode progress. The hearing loss slowly becomes permanent. There is never a loss of consciousness. Rarely the giddiness is so sudden that patient may fall down.

Causes

The exact cause of Meniere’s Disease is not known. It is hypothesized that there is an increased fluid collection in the inner ear called Endolymphatic Hydrops. Till the pressure in inner ear is high, patient is symptomatic. Once the pressure reduces, patient improves. All efforts at treatment are made to prevent and treat the increase in inner ear pressure.

Evaluation

During the episodes of giddiness, tinnitus and hearing loss or fullness in the ears, Audiometry shows a low frequency sensorineural hearing loss, VNG and ECoG will be positive for vertigo due to Meniere’s Disease. Between the episodes the results may be normal. MRI Brain and ECG may be advised to rule out brain stroke and heart attack respectively.

Treatments

Commonly prescribed drugs include Betahistidine (VertinTM) and Prochlorperazine (StemtilTM) to control the giddiness. Diamox TM may be prescribed to reduce the collection of fluid in the body. A salt restricted diet is advised. If any other specific trigger is identified, the same is avoided. Low doses of medicines are continued to prevent further episodes. Regular walks and exercise are recommended. Normal day to day activity need not be restricted. Driving, climbing heights or carrying firearms are to be avoided.

Surgery is recommended to people who receive little or no benefit from medicines. Injection of steroid into the middle ear space allows it to slowly seep into inner ear and has shown beneficial effect in many patients. Other surgeries aim to control the production and outflow of inner ear fluid. Patients with severe hearing loss may be advised more radical surgeries.

While Meniere’s Disease is a common cause of giddiness. Every vertigo is not due to Meniere’s Disease. A combination of clinical examination and testing helps in accurate diagnosis. Most episodes can be easily controlled and prevented. Surgery is the last resort in resistant cases.

Wastewater Treatment: Mitigating Health Risks and Promoting Well-being

Wastewater treatment is an important but frequently disregarded feature of contemporary society. It is essential for preserving public health and advancing general wellbeing. This blog will discuss the significance of wastewater treatment, its effects on human health, and how it helps create a more sustainable and healthy future.

Hazards of Untreated Wastewater That Go Unnoticed

Wastewater that hasn’t been treated seriously endangers people’s health. It has a diverse range of contaminants, including as germs, viruses, chemicals, and other dangerous materials. Numerous health problems may arise when this tainted water gets into the environment or our water supply.

The main risk posed by untreated wastewater is waterborne illnesses. Typhoid, cholera, and hepatitis outbreaks can quickly spread through contaminated water supplies, affecting entire populations. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), 2.2 million people die from diarrheal diseases each year, primarily as a result of contaminated water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene—problems that are directly related to untreated wastewater.

Keeping Drinking Water Safe

Protecting our drinking water is one of the most important functions of wastewater treatment. Before wastewater is released into rivers, lakes, or seas or recycled for non-potable uses, wastewater treatment plants remove contaminants, such as pathogens and chemical pollutants. This guarantees that the water we drink is secure and devoid of dangerous toxins.

Furthermore, in regions where water is scarce, treated wastewater can be a useful resource. Wastewater can be filtered using cutting-edge treatment techniques to the point where it can be used for a variety of non-potable tasks, including irrigation, business operations, and even indirect potable reuse. This preserves freshwater resources and lessens the strain on ecological systems.

Ecosystem health and environmental protection

The health of our ecosystem is significantly impacted by efficient wastewater treatment. Eutrophication of lakes and rivers can occur when untreated wastewater is dumped into natural water bodies. The growth of hazardous algae is encouraged by excess nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which can lower oxygen levels and destroy aquatic life.

Additionally, untreated wastewater may include dangerous compounds and heavy metals that kill fish and other creatures by disrupting aquatic ecosystems. Wastewater treatment procedures eliminate or neutralise these damaging elements, aiding in the preservation of our waterways’ biodiversity.

Keeping Antibiotic Resistance from Spreading

A significant public health problem is the prevalence of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistant microorganisms in wastewater. Antibiotics may wind up in wastewater when they are incorrectly disposed of or excreted by people and animals. By destroying antibiotics and eradicating antibiotic-resistant microorganisms, wastewater treatment facilities can be extremely effective in preventing the spread of antibiotic resistance.

Treatment facilities protect the potency of these essential medications in medical care by eliminating antibiotics from wastewater, which lowers the selective pressure for antibiotic resistance. Through ensuring that antibiotics continue to be effective against bacterial illnesses, this in turn contributes to better public health outcomes.

Future Cleaner and Safer

Investing in wastewater treatment is a step towards a more fair and sustainable future in addition to being a concern of public health. Despite being a fundamental human right, billions of people worldwide still do not have access to clean sanitation and wastewater treatment.

Infrastructure improvements for wastewater treatment can have significant advantages. In especially in vulnerable populations, they lessen the burden of waterborne infections by generating jobs, promoting economic growth, and doing so. Additionally, the employment of cutting-edge treatment technology can improve the energy and environmental sustainability of wastewater treatment, supporting international efforts to battle climate change.

Conclusion

Although wastewater treatment may not seem like a glamorous subject, it is nonetheless extremely important. It serves as a cornerstone of environmental and public health protection, preserving our water supplies and advancing societal well-being as a whole. Investments in wastewater treatment are investments in a cleaner, safer, and more sustainable future for all, as we continue to face water scarcity and environmental problems. We can make sure that wastewater treatment continues to reduce health risks and advance wellbeing for future generations by acknowledging its crucial role and encouraging its development and improvement.

The author is a head of Sales and Entrepreneurship

As we age, our bodies undergo various changes, and one of the most concerning is the gradual loss of muscle mass and strength, a condition known as sarcopenia. It is a natural part of the aging process characterized by the loss of muscle mass, strength, and function. It typically begins in our 30s, but its effects become more pronounced as we enter our 50s and beyond. Contributing factors include hormonal changes, decreased physical activity, and inadequate nutrition. Muscle loss can lead to a decline in mobility, making everyday activities more challenging and increasing the risk of falls and fractures. With less muscle mass, the body burns fewer calories at rest, potentially leading to weight gain and obesity-related health issues. Sarcopenia can result in frailty, making individuals more vulnerable to illness and decreasing their ability to recover from injuries or surgeries.

Sarcopenia and osteoporosis often coexist and exacerbate each other’s effects. Loss of muscle mass and strength can contribute to balance and stability issues, increasing the risk of falls and fractures (osteoporosis). On the other hand, fractures due to osteoporosis can result in reduced mobility, leading to muscle disuse and further exacerbating muscle loss (sarcopenia)

Nutrition plays a crucial role in combating sarcopenia. Incorporating the following foods into your diet can help support muscle growth and maintenance:

Protein and essential amino acids: Ensure an adequate intake of high-quality protein sources like lean meats, fish, eggs, dairy products, and plant-based options like legumes and tofu.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids: These fats, found in fatty fish like salmon and walnuts, have anti-inflammatory properties that can help protect muscle mass.

Vitamin D: This vitamin is essential for muscle function and can be obtained through sunlight exposure and foods like fortified dairy products and fatty fish.

Antioxidants: Foods rich in antioxidants, such as fruits and vegetables, can help reduce inflammation and protect muscle tissue.

Nutraceuticals are bioactive compounds found in certain foods or available as supplements that can have positive effects on muscle health. Known for its role in energy production, creatine supplementation has been shown to improve muscle strength in older adults. Collagen peptides may support muscle mass and function while also benefiting joint health. HMB (Beta-Hydroxy Beta-Methylbutyrate) helps reduce protein breakdown and promote muscle growth. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), a powerful antioxidant properties and may enhance mitochondrial function, which is vital for muscle energy production.

By maintaining healthy, balanced diet rich in muscle-supporting nutrients and considering the use of nutraceuticals, individuals can take proactive steps to preserve their muscle health and enjoy a higher quality of life as they age.

Dr Anish Desai is MD, Clinical Pharmacologist and Nutraceutical Physician, Founder and CEO, IntelliMed Healthcare

Solutions.

The yearly observance of World Suicide Prevention Day on September 10th stands as a poignant annual event underscoring the notion that support is frequently closer than we realise, whether it comes from a dependable friend, relative, or professional.

Understanding the Crisis

Suicide is a multifaceted issue, often entangled with mental health challenges, external stressors, and personal battles.

The Lifeline Within Reach

There is often a lifeline extending towards us—an empathetic friend, a supportive family member, or a seasoned professional. These individuals offer more than a mere safety net; they extend a lifeline teeming with emotional support, guidance, and a compassionate, non-judgmental presence.

The Mighty Power of Connection

Human connection wields an incredible influence. A heartfelt check-in with a friend, a candid sharing of your emotions with a loved one, or the decision to seek professional assistance can work wonders in someone’s life.

Breaking Down the Stigma

Its goal is to foster empathy, understanding, and acceptance, emphasizing that reaching out for assistance demonstrates strength and resilience rather than vulnerability.

The Importance of the Day

In a world where mental health concerns often linger in the shadows, World Suicide Prevention Day beckons us to step into the light, to break the silence, and to be that lifeline for someone in need. By Dr. Neerja Agarwal

Everything you should know about Ayurvedic treatment before you go for it

Having stood the test of time, Ayurvedic treatment provides exceptional results in managing and treating different types of disorders holistically. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is one such example of a life-threatening disease that can be effectively managed with Ayurvedic intervention. While an increasing number of people are willing to embrace the Ayurvedic way of life to fight diseases or stay healthy in general, some misconceptions still surround this ancient system of medicine and the way it works. People must be aware of the approach Ayurveda takes so that they can avail the maximum benefit from it.

Ayurveda focuses on your ahara and vihara

The food you consume (ahara) and the lifestyle you have (vihara) play a crucial role in directing the outcome of your treatment. Ayurveda requires that you bid adieu to unhealthy habits like smoking and drinking excessive alcohol as they weaken the immune system and thus make you vulnerable to many infections and diseases. In addition, your body’s circadian rhythm has a lot to do with your overall health. Ayurveda encourages an uninterrupted quality sleep of 6-8 hours to optimize the benefits of the treatment.

Ayurveda is for those with patience

Yes, that is correct and a requirement if you are willing to embrace Ayurveda. The ancient system of medicine does not believe in quick fixes but rather in providing benefits that go a long way in preventing, managing, and treating the disease from the ground up. Observing visible results might take some time as instead of only treating symptoms, Ayurveda tries to address the underlying cause of an illness. For best outcomes, patience and consistency are crucial.

Ayurvedic formulations contain more than just herbs

Many people are under the impression that Ayurvedic formulations contain only herbs. While this may be the case in certain formulations, it is not always true. Oftentimes, Ayurvedic formulations are a concoction of active ingredients and components from animal, mineral, or plant origin.

Ayurveda can be integrated with other medicines

People can avail themselves of the benefits of Ayurveda while also sticking to conventional medicines. However, this has to be in the knowledge of your treating doctor. This is important as the medicines you are taking can interact with the action of other medicines and only a doctor can help you choose the right treatment regimen that has the highest chances of success in your case.

Ayurveda treatment could utilize acupuncture and yoga

Ayurveda believes in curing the imbalances (doshas) of the body. It does so by making use of acupuncture and yoga in addition to diet and medications. These approaches synergistically stimulate the body to flush out toxins, thus healing the body naturally. Body movement through yoga helps the release of hormones called endorphins in the body that reduces stress and relieves pain, thus enhancing the treatment outcome.

Diagnostic tests are needed in Ayurveda as well

As in the allopathic system of medicine, an Ayurvedic doctor would also do some preliminary tests and based on the reports would furnish a diagnosis and then work out the treatment regimen best suited for that individual case. It is important to understand that no two individuals will have the same treatment plan as Ayurveda is personalized medicine. Although Ayurveda uses natural products to cure diseases, self-medication is a definite no as all formulations may not be beneficial to everyone. Therefore, consulting a professional practitioner is a must.

Summing up

Embarking on an Ayurvedic journey calls for the need to know Ayurveda better and decide for yourself if you are ready to embrace the life Ayurveda demands. If you are willing to make a few healthy changes in your diet and lifestyle, you are more than ready to start an Ayurvedic treatment for holistic well-being or treating any condition. One must seek medical help from an experienced registered Ayurvedic medical practitioner only. Ayurveda alone or in combination with conventional medicine can work to contribute to comprehensive care.

The author is Founder & Director of Karma Ayurveda

Peripheral artery disease (PAD) is plaque (atherosclerosis) buildup in your leg arteries. This makes it harder for your blood to carry oxygen and nutrients to the tissues in those areas. PAD is a long-term disease, but you can improve it by exercising, eating less fat and giving up tobacco products.

How common is peripheral artery disease?

PAD is common, affecting between 4.1 to 5 crore Indians. Actual numbers are probably higher as most of the times its underdiagnosed disease. In PGIMER, We usually see more than 100 patients OPD everyday suffering with PVD related issues.

How does peripheral artery disease affect body?

The typical symptom of PAD is called claudication, a medical term for pain in your leg that starts with walking or exercise and goes away with rest. The pain occurs because your leg muscles aren’t getting enough oxygen.

The dangers of PAD extend well beyond difficulties in walking. Peripheral artery disease increases the risk of getting a nonhealing sore in your legs or feet. In cases of severe PAD, these sores can turn into areas of dead tissue (gangrene) that can sometimes lead to amputation of toes, foot or leg.

What are the stages of peripheral artery disease?

Healthcare providers can use two different systems — Fontaine and Rutherford — to assign a stage to your PAD. The Fontaine stages, which are simpler, are:

I: Asymptomatic (without symptoms).

IIa: Mild claudication (leg pain during exercise).

IIb: Moderate to severe claudication.

III: Ischemic rest pain (pain in your legs when you’re at rest).

IV: Ulcers or gangrene.

SYMPTOMS AND CAUSES

The first symptom of PAD is usually pain, cramping or discomfort in your legs or buttocks. This happens when you’re walking and goes away when you take rest.

What are the typical symptoms of peripheral artery disease?

A burning or aching pain in your feet and toes while resting, especially at night while lying flat.

Cool skin on your feet.

Redness or other color changes of your skin.

More frequent skin and soft tissue infections in your feet or legs

Toe and foot sores that don’t heal.

Half of the people who have peripheral vascular disease don’t have any symptoms. PAD can build up over a lifetime. Symptoms may not become obvious until later in life. For many people, symptoms won’t appear until their artery narrows by 60% or more.

Talk to a Vascular surgeon if you’re having symptoms of PAD so they can start treatment as soon as possible. Early detection of PAD is imperitive for starting timely treatment to avoid severe complications like a heart attack or stroke.

What are the complications of peripheral artery disease?

Without treatment, people with complicated PAD may need an amputation — the removal of part or all of your foot or leg (rarely your arm), especially in people who also have diabetes.

Because your body’s circulatory system is interconnected, the effects of PAD can extend beyond the affected limb. People with atherosclerosis of their legs often have it in other parts of their bodies.

What is the most common cause of peripheral artery disease?

Atherosclerosis that develops in the arteries of your legs — or, less commonly in your arms — causes peripheral arterial disease. Like atherosclerosis in your heart (coronary) arteries, a collection of fatty plaque in your blood vessel walls causes peripheral vascular disease. As plaque builds up, your blood vessels get narrower and narrower, until they’re blocked.

What are the risk factors for peripheral artery disease?

Tobacco use is the most important risk factor for PAD and its complications. In fact, 80% of people with PAD are people who currently smoke or used to smoke. Tobacco use increases the risk for PAD by 400%. It also brings on PAD symptoms almost 10 years earlier.

Compared with non-smokers of the same age, people who smoke and have PAD are more likely to have heart attack or stroke and have a limb amputation.

Regardless of your sex, you’re at risk of developing peripheral arterial disease when you have one or more of these risk factors:

Using tobacco products (the most potent risk factor).

Having diabetes

Being age 50 and older.

Having a personal or family history of heart or blood vessel disease.

Having high blood pressure (hypertension)

Having high cholesterol (hyperlipidemia).

Having abdominal obesity.

Having a blood clotting disorder.

Having kidney disease (both a risk factor and a consequence of PAD).

DIAGNOSIS AND TESTS

A vascular surgeon or vascular care provider(interventional radiologist/cardiologist) will perform a physical exam and review your medical history and risk factors. They may order non-invasive tests to help diagnose PAD and determine its severity. If you have a blockage in a blood vessel, these tests can help find it.

Ankle-brachial index (ABI).

Pulse volume recording (PVR).

Vascular ultrasound.

You may also need an invasive test called an angiogram to find artery blockages.

MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

Can peripheral artery disease be reversed?

Yes. Some studies have shown that you can reverse peripheral vascular disease symptoms with exercise and control of cholesterol and blood pressure.

With early diagnosis, lifestyle changes and treatment, you can stop PAD from getting worse.

Lifestyle changes

Quit using tobacco products- Ask your physian about smoking cessationprograms.

Eat a balanced diet that’s high in fiber and low in cholesterol, fat and sodium. Limit fat to 30% of your total daily calories. Saturated fat should account for no more than 7% of your total calories. Avoid trans fats, including products made with partially hydrogenated and hydrogenated vegetable oils.

Exercise-Start a regular exercise program, such as walking. Walking can help treat PAD. People who walk regularly can increase the distance they’re able to walk before their legs hurt.

Manage other health conditions, such as high blood pressure, diabetes or high cholesterol.

LIVING WITH IT

It’s important to take good care of your feet to prevent nonhealing sores. Foot care for people who have PAD includes:

Wearing comfortable, appropriately fitting shoes.

Inspecting your legs and feet daily for blisters, cuts, cracks, scratches or sores. Also check for redness, increased warmth, ingrown toenails, corns and calluses.

Not waiting to treat a minor foot or skin problem.

Keeping your feet clean and well moisturized. (Don’t moisturize an area with an open sore.)

Cutting your toenails after bathing, when they’re soft. Cut them straight across and smooth them with a nail file.

In some cases, your healthcare provider may refer you to a vascular surgeon (foot expert) for specialized foot care – especially if you have diabetes.

When should one see Vascular Surgeon or Vascular Specialist?

Contact your healthcare provider if you:

Get a bad infection in a sore on your foot. The infection can expand into your muscles, tissues, blood and bones. If your infection is severe, you may need to go to the hospital.

Can’t walk around enough to do normal activities.

Have pain in your legs when you’re resting. This is a sign of poor blood flow.

The author is Vascular Surgeon, at PGIMER Chandigarh

There are so many of us Indians who love spicy and oily food, without knowing what it might cause in our bodies. Ulcers are often the result of inadequate presence of the bicarbonate ions in the stomach lining. Hence, on account of inadequate bicarbonate ions to neutralize the H+ ions in the acidic secretions of the gut, stomach acid has the capacity of corroding the stomach lining. This gives rise to ulcers.

These ulcers can be caused by various factors, such as the Helicobacter pylori bacteria, prolonged use of certain medications like NSAIDs, excessive alcohol consumption, and chronic stress.

Irregular meal timings combined with having large meals at a time all play a role in disturbing the functioning of the normal digestive system. Paying proper attention to regularizing meal timings & minding the portion size of meals can help reverse gut disorders such as peptic ulcers.

Incorporating these Indian foods that have shown promise in soothing stomach ulcers, is backed by scientific evidence.

1.Curd,

2.Indian gooseberry,

also known as amla, is a potent source of vitamin C and antioxidants. It has been traditionally used to treat various digestive ailments. Studies suggest that amla’s anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties contribute to the healing of stomach ulcers.

3.Coriander

4.Coconut water

5.Honey

While the aforementioned Indian foods show promise in soothing stomach ulcers, it is essential to remember that individual responses may vary. Consulting a healthcare professional and adhering to prescribed medications is crucial for effective ulcer management. Additionally, avoiding spicy, acidic, and fried foods is recommended to prevent exacerbating ulcer symptoms.

Dr Anish Desai is MD, Clinical Pharmacologist and Nutraceutical Physician, Founder and CEO, IntelliMed Healthcare Solutions.